Del Kathryn Barton thought she was psychologically resilient enough to make a film that was informed by a traumatic experience from her own life.

She was mistaken.

The Australian artist’s debut as a film director and co-writer, Blaze, is not autobiographical, but it is informed by something that happened to Barton as a child. It tells the story of a 12-year-old girl named Blaze who witnesses the rape and murder of a woman.

“I had done decades of therapy, and I felt ready to tell the story,” says Barton, 49, seated in her studio in Paddington in inner Sydney.

“But, no, I was totally unprepared for the degree to which it would re-trigger me, and I’ve had some really, really hard moments, and I want to be honest about that,” she says. “I went in feeling so resilient, and I’m back in therapy … I’m in a very supportive place, so I feel very blessed, but no – it’s been really, really hard, and I don’t say that lightly.”

Blaze, which opens this month, is a hybrid of naturalistic drama and fantasy sequences, which deploys elaborate costumes and stop-motion animation. It stars Julia Savage in the title role, who was 13 when the film was made; and Orange is the New Black star Yael Stone as Hannah, who is raped and murdered in a Sydney laneway.

Barton does not want to discuss the specifics of her own trauma, but confirms it happened when she was Blaze’s age in the mid-1980s, when the family lived in Castle Hill.

When Stone first met Barton, she had already declined the role, finding the film’s subject matter compelling but the part “horrific”. She wanted to meet Barton anyway, and recalls: “I was in big trouble because she was just so brilliantly fascinating and warm and interesting and captivating.” She accepted, and told Barton she wanted to make sure she could mentor whoever played Blaze, given the “pitfalls” that exist for young actors in the industry.

Stone was “incredible”, Barton says. “She really wanted me to know – and it was a huge gift – that she’d never suffered any kind of [physical] sexual violence, and that she really wanted to bring herself as a conduit for other women’s stories. That was very meaningful to her.”

In 2018, Stone alleged that Geoffrey Rush engaged in inappropriate behaviour when the pair were acting in a 2010 production of The Diary of a Madman – claims which he denies. “I can’t deny that’s part of my story, my public story,” she says now, praising the women who have led the #MeToo conversation in Australia.

“Certainly people very close to me have experienced sexual abuse and sexual violence. There are many doors to the house, and for some people it’s about policy work and it’s about reform, and for Del it’s through her art – and obviously the film is this beautiful testament to healing through creativity.”

Barton describes Savage as a “fierce little lady”, who “identified as a feminist from the age of five”. She clinched the audition by performing a “rage dance”, which is seen towards the end of the film – and which the director believes connects audiences to the “emotional and physical experience” of trauma.

Through the film the character of Blaze finds comfort in a large, benevolent dragon called Zephyr, represented in a four-metre-high costume designed by Barton as a nostalgic nod to her own childhood and “that beautiful idea that, as we transition into adulthood, we don’t let our inner dragons crawl into their caves and cease their fearless roar”.

So is Blaze’s story also Del Kathryn Barton’s story, or is that too literal a reading? “It’s a little bit of both,” says Barton.

“Definitely I never want to say that the film is autobiographical, but it is informed by personal experience.”

When Barton was young, her parents Wesley and Karen moved their three children to an Angora goat farm by the Hawkesbury River, where they lived in a large circus-like tent for a couple of years while Wesley fixed up an old farmhouse. “We moved to the country as a response to what happened [to me] in the suburbs. That was my dad’s way of coping.”

Now the film is finished, Barton is undecided whether she will show it to her “eccentric” father, who is unwell. “I almost want to protect him from that experience, I suppose,” she muses. When she speaks of her late mother, Karen, she apologises for looking behind me in the studio, “like there’s a ghost or something”.

Both her parents were teachers who were idealistic about education; Karen worked in a Steiner school and advised her daughter to be true to her passion for art. Barton – a two-time Archibald prizewinner who is now preparing for her first Los Angeles exhibition – believes imagination is crucial to healing.

“I’m on meds now, and it’s a game-changer for me – I’m definitely not anti-establishment or anti-psychiatry,” she says. “[But] we live in … an overly anaesthetised society that teaches people to fear pain, to fear chaos and the trauma body – fuck, life’s hard man; life’s confusing – [rather than] sit in uncomfortable places and remain calm and find magic there.”

Barton has long suffered social anxiety, which is at odds with her extroverted nature and her bellowing laugh.

“I know, and I almost kick myself a bit, because I know I fake it really well,” she says. “But I do genuinely love people and I feel like, especially in a directing capacity, like, you really need to bring a certain energy to a room to carry people, but it takes a lot out of me.”

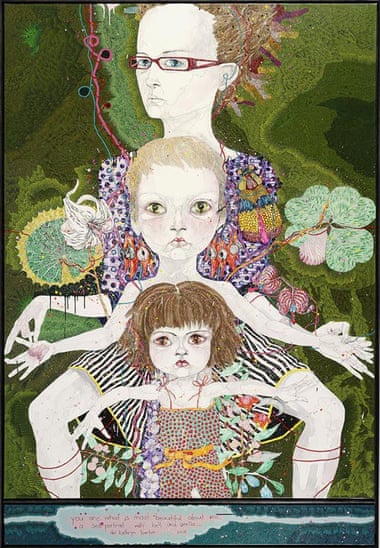

Barton is married to a “pathological, full-blown nerdy introvert”, a financial services executive she credits with helping her to understand herself. The couple have two children, a son and a daughter, who both featured in Barton’s 2008 Archibald prizewinning self-portrait.

Barton sees female rage against the silencing of women as an important “generative” force.

“For me there’s a difference between anger and rage,” Barton says. “[Rage is] when I’ve managed to do the cognitive work, identify more what’s happening in the emotional self … and through feeling it and expressing it on one level, I’m releasing it, so that it doesn’t cripple me.”

She sees it as a collective energy too, with vast potential: “If it’s out in the open, and acknowledged as being a valid emotion, then I just think a lot of healing can happen at that point.”

Yael Stone, who “totally validates Del’s experience”, has a different response: “For me, rage has been quite destructive in my life, even personal rage,” she says. “I think rage as a motivator can be very powerful … but rage alone for me has been caustic.” Being able to access her own rage is “an amazing gift” when so many women can’t – “but also a power to be wielded with a sense of responsibility”.

Playing Blaze’s caring single father is Simon Baker, baffled about how he can help his daughter cope with what she has witnessed. One purpose of the film, Barton says, is to show people how to help, and listen to, those who have been traumatised.

“We live in a world where men have been taught to fix things, and really, all Blaze needs from [her father], the greatest gift that he can offer her, is just to be present to her understanding of her experience, and attempt to hold a place for that – to not try and protect her from it, to not try and tell her what she’s feeling.

“That takes time, and there’s no answers – and everyone’s healing journey is idiosyncratic and uniquely theirs.”